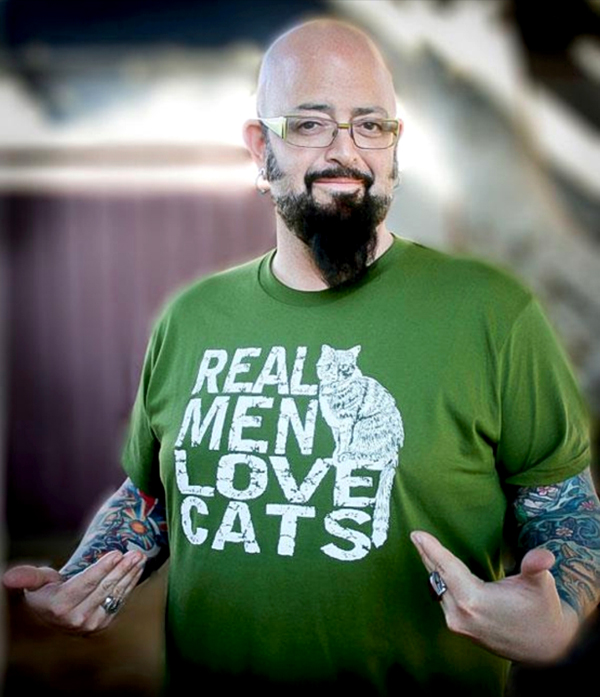

Some people (myself included) have joked that Jackson Galaxy and I are different versions of the same guy. On the surface we’re each big, bald-headed, cat-loving guys with distinctive eyewear, quasi-retro looks, and backgrounds in art and performance who live in the public eye to varying degrees. (Galaxy hosts Animal Planet’s My Cat from Hell and wrote a book about his experience called Cat Daddy; I write this column.)

But after talking to him on the phone, it felt like reconnecting with an old friend. Our ideas on appearance, intellect, animals, creativity, metaphysics, and how it all fits together are remarkably similar. (To add “uncanny” to the mix, Galaxy is recovering from back surgery, and on the day of our interview I was home with a pretty severe back injury.)

I’ll add that Galaxy is far more advanced than I am on a lot of fronts. Our conversation made it clear: He is a man who’s living the life the universe wants him to live — using everything he’s learned in life to inform what he does. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

On paradoxes and assumptions

In Cat Daddy (which recently was released in paperback), Galaxy describes himself as “sensitive” and introspective, and definitely not a confrontational person, despite his appearance that might suggest otherwise. I’ve long seen myself in a similar way for similar reasons. I asked Galaxy how this paradox applies to men who love cats and to cats themselves.

“When you’re a big guy [Galaxy was six feet tall by age 12 or 13], you’re held to a certain stereotype,” he said. “But by the time I was 16, I was the introspective singer/songwriter guy.”

He was in a band, and he also went on to study theater and performance art. These are not the first things that come to mind when someone sees a big, butchy man. (Neither are cats.) Yet Galaxy says he has embraced this paradox.

“I’m psyched to confuse you,” he says. “The first time a four-syllable word comes out of my mouth, I love to see that look on your face.”

He says mistaken assumptions are also often made about cats — that cats are aloof, that they can’t be trained, that they prefer to be by themselves, that they’re not sensitive animals — and he revels in showing people what they didn’t expect.

Why?

“When you humble someone by blowing their assumptions out of the water, you show them mystery,” he said.

And cats are all about mystery.

On cats and men

Speaking of mystery, I’ve long been puzzled why many people contend that men and cats just don’t go together. I asked Galaxy about this, and he said he can see where such ideas originate.

“I’ve always seen [cats] as more of a feminine thing,” he said. “I’ve seen women as more appreciative of mystery, where the male psyche is more of the conqueror — as in, ‘Let’s take apart the radio to see how it works.’ We know how dogs work [more than we understand cats], so they’ve been more of a guy thing.”

But more men are coming to embrace the mystery. On a recent book tour he saw more and more men in audiences whose numbers were in the hundreds — and lots of them standing up to be recognized as cat lovers.

“Mystery serves a great purpose in our lives,” he said. “Cats, to me, they really symbolize that.”

On being a performer

Another memorable part of Cat Daddy involves Galaxy’s background as a performer. I asked him to describe some of the ways this experience helps him.

“I always thought my calling was in front of an audience,” he said. “It’s the only thing I thought I would be.”

This, he said, has kept him grounded as My Cat From Hell has become more popular.

On a deeper level, he says it has helped him evaluate situations among people and animals, because performers study the behavior of those around them so they can incorporate it into their work.

An example all things working together, he said, involves a woman on his show named Megan and her cat Fi, a purebred Persian who had bounced between homes and shelters and who refused to use a litter box.

“Part of what my life as a performer and a shelter worker is,” he said, “it’s to allow Megan and my audience to appreciate this cat for being more than a poo-and-pee machine, and to take as much as we know and turn her life into a story.”

So he asked Megan to write Fi’s story — from Fi’s point of view.

“Megan demonstrated incredible dedication,” he said, “and she had also resigned herself to being the person who cleans up after the cat.”

She invested her empathic skills in writing the story, and she and Galaxy eventually got Fi to use a litter box.

“I can promise you that cat won’t be looking for a sixth home,” he said. “That episode embodies how my life as a performer and an artist informs this work.”

“This why I live this life,” he continued. “It’s amazing when the universe offers you proof, that there is a reason, there is a reason you were sent down this path.”

Galaxy said that his celebrity status keeps him honest in very important ways.

“I’m held to a higher standard … by the people who work in the industry I love so much,” he said. “I can’t get away with being a prima donna. And I love that.”

On what we owe cats

Since I’ve worked at Catster I’ve learned just how serious the cat-overpopulation problem is — and also how serious some people are about cats. Some can be quick to condemn anyone who disagrees with them on any point. So I asked Galaxy: What do we owe cats?

He was pretty clear: Help solve the overpopulation problem any way you can.

“You don’t have to be the Mother Teresa of cats,” he said, “but it means, for example, you don’t walk by the strays. You go and you do something about it.”

Asked whether he recommends people volunteer at shelters — or seek full-time work there when possible, as he did — his answer was simple: “Absolutely.”

Among useful things most anyone can do is spending an hour here and there petting shelter cats to help socialize them. This makes cats happy, and a happier cat is a more adoptable cat.

“You can bring peace to these guys where they most need it,” he said.

Galaxy also recommends reading and learning as much as you can about cat overpopulation, which is one of the ways he learned.

As for those who condemn others in the name of loving cats, he says, “Get out there and prove it.”

“If you love cats so much, I’m not even going to listen to you unless you’re doing something to help them,” he said. “The people who feel entitled to go berserk when they’re not out there doing something, that bothers me.”

Yet Galaxy sees signs that his efforts are paying off. For example, when he has helped teach grade-school kids about pets and overpopulation, some of them approach him afterward and ask how they can get involved and eventually work to help cats like he does.

“It makes you want to cry,” he said.

On Internet flame wars over cats

During my time at Catster I’ve been reminded that a lot of people have strong ideas about cats — and that some people can be quick to condemn anyone who disagrees with them. It’s the exception rather than the rule, but it drives me to distraction nonetheless when people heap shame on those who do things in a different way. So I asked Galaxy his feelings on such behavior and what we might do to get past it.

He began by saying there is a good side to people who voice strong opinions online: It shows that they care, and it also indicates that those people’s animals will spend their entire lives in a home rather than in a shelter.

Just the same, he says to such people, “Get out there and prove it” by doing work at a shelter, or trap-neuter-return, or anything that helps fight overpopulation.

He mentioned a commenter on his YouTube channel who repeatedly advocates declawing surgery. The person cites studies and statistics, Galaxy said, while using scientific words to describe the various parts of feet and claws involved, such as “distal phalanx.”

“That attitude is removed from the animal’s experience enough to be dangerous,” he said. “It’s like they’re spending all their spare time researching cat anatomy,” while ignoring a basic fact about how the procedure affects cats: “It hurts!”

Such an approach also reflects a worldview in which humans — because we’re the dominant species on the planet — are entitled to do essentially whatever we want to other animals.

“She [the commenter] is talking about dominion,” he said, as in, “‘We have the authority to do to them what we want.’ A lesson that animals can teach us is that we’re not the be-all-end-all. It’s not all about us. We’re not the center of the universe.”

Maintaining the focus on animals is crucial, he said. He cites an example from My Cat From Hell where condemnation was definitely miscast. It involved a couple named Lucas and Candice and a 23-year-old cat named Pump. Pump had been adopted from an ex-girlfriend of Lucas, and after having some issues with the cat, Candice bonded with Pump and agreed to keep him.

Soon after filming ended, though, she sent Pump to live with her mother-in-law — and that started a firestorm on the web. The fury was pointless, Galaxy said, because in the end, Pump was in a good home with a person who loved him. The people who were so angry considered Candice’s broken promise more than they considered the well-being of the cat — which made no sense.

“It’s easy to succumb to the emotions of condemnation; much harder to expand our circle of love and access the bigger picture,” Galaxy wrote on his website after the outpouring of emotion over Pump.

On “cat people” and stereotypes

On a recent book tour for Cat Daddy, Galaxy said, some of the audiences were hundreds of people strong. He said the energy was remarkable, mostly because cat lovers have far fewer chances to express their species love in public than, say, dog lovers.

“People who really adore cats never have an excuse to get out and celebrate that,” he said. “There’s no cat park — no cat playdate.”

Because of this, we as a society “allow the stereotype to perpetuate of crazy cat people who never leave their homes, and who sit rocking slowly in the dark while petting their cats.”

Just the same, people who love cats can do themselves and animals a disservice by playing into the stereotype too much.

“There’s a level of species-ism,” he said, “that says if you love one [kind of animal] then you don’t like others.”

Galaxy encourages people to be more inclusive, “because it’s about paying our karmic debt to animals.”

People who take a more exclusionary approach are “acting sort of from a luxury standpoint. The bottom line is that if we all don’t have at least one cat in our life, they will be dying in shelters or on the street, because that’s the extent of the overpopulation crisis.”

“If you say only this type of person deserves a cat, then you’re missing that.”

To be sure, Galaxy says, “Own your inner crazy cat lady, but bring more people into the club. Don’t celebrate and exclude others at the same time.”

The current cats — and dogs — in his life

Galaxy lives with eight cats and two dogs. Three cats are his. Velouria is 21. She’s his last link to his life in Boulder, Colorado, where he first worked in a shelter. Chuppy (also known as Chippy, or Chips) is 19. “Her job is to sleep.” Caroline (“She’s our spooky one”) is four. She was adopted as a feral, and she gets to teach other ferals that they can be pets as well, Galaxy said.

Three cats he “adopted” when he and his girlfriend moved in together. They are Pishi (which is a Farsi word for “kitty cat”), Barry (as in Barry White — so named because of his deep-voiced meow), and Lily (Barry’s sister).

The final cats, two ferals who live outdoors, are called Sophie and Oliver.

The two dogs are Rudy, a blind Jack Russell Terrier who’s about 8 or 9 and who Galaxy has had for a while, and Mooshka, a 65-pound Chow mix brought to the house by his girlfriend.

The future of My Cat From Hell

Shooting for a new season begins pretty soon, in the fall, and when we spoke in late June he was casting for those episodes. Galaxy says they will necessarily be within the continental U.S., but beyond that he’d love to bring the show to the United Kingdom, Australia, and South America, among other places. Cities that might be included in the upcoming season include Austin, Boston, Chicago, and San Diego.

“Austin is practically a no-kill city,” he said. “Anywhere where the shelter scene turns me on is where I want to be.”

Wildcard

Galaxy said one of the best questions he got on his book tour was, “If you were reincarnated as an animal, what animal would you like that to be?”

His answer? An elephant.

“Their mystery is so amazingly deep — their communication skills, their inner life,” he said.

Rather than studying elephants to understand them better, he said, “I’d just want to be a part of that.”

What’s next for the Cat Daddy

What’s next for the Cat Daddy

Galaxy aims to establish a nonprofit group that will help shelter workers deal with overpopulation and end euthanasia. He says he’s certain this solution will come from the inside.

“It [the nonprofit] will concentrate on elevating the shelter worker,” he said, “because the final push of the no-kill solution begins and ends with people who work in the system — not from a think-tank, not from outside, but from inside.”

If a shelter worker has an idea on how things can be done better, Galaxy said, that person deserves grant money, for example, and support in developing that idea. Timing is often crucial, he said, because shelter work is so difficult, and many people can’t do it indefinitely.

“We can’t afford to take our best and brightest and accept the fact that we’re going to lose them to burnout,” he said.

Featured Image Credit: Esin Deniz, Shutterstock